James Holmes, 24, the orange-haired, accused mass killer, has today been charged with two separate counts of first-degree murder for each of the twelve June 20 deaths inside the Aurora movie theater. The first charge alleges his intention to cause harm; the second, his acting with extreme indifference to human life.

James Holmes, 24, the orange-haired, accused mass killer, has today been charged with two separate counts of first-degree murder for each of the twelve June 20 deaths inside the Aurora movie theater. The first charge alleges his intention to cause harm; the second, his acting with extreme indifference to human life.

Court video of the accused reveals a man clearly struggling to maintain focus upon the ongoing proceeding; though the cause and even the authenticity of his disorientation is yet unknown. Whether his courtroom behavior reflects a pre-trial strategy orchestrated by him and his defense counsel or a genuine manifestation of a mental disorder, odds are good that a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity will be forthcoming.

Need it be said, however, that mental illness is real? And whether suffering from a psychotic episode or from permanent schizophrenia, the severely afflicted experience a partial break from reality. This fact may seem contestable: They navigate among us, still able to perceive both the objects and the people around them, at least superficially communicating and relating.

But beneath the surface, false internal stimuli are blocking them from an ongoing emotional tracking of, or a personalized integration with, the complex yet mundane, subjective world that forms the basis for our daily associations.

We ought not condemn their actions, therefore, as entirely or even predominantly willful, even under tragic circumstances like the Aurora shooting spree.

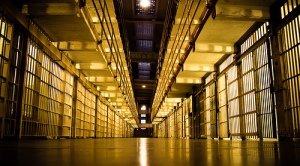

Our compassion, however, must not extend so far that we release those judged mentally ill, thus not guilty of their crimes, back into the community within a shorter time frame than would be a competent defendant convicted of a similar offense. The protection of the general public is the primary justification for the continued existence of government itself.

Severe mental illness has many treatments but few to none have cures. And our bodies become habituated to even the most powerful medications when taken over longer periods of time; so that even strong anti-psychotic medications likely will lose their full effectiveness. Mental patients, too, once discharged often decide to take themselves off of their prescribed medications.

For the sake of ensuring public safety, then, it would be irresponsible for the government not to confine the offending mentally ill to institutions, either until cures for their disorders are developed; until their conditions naturally remit, or — at a bare minimum — until such time as a competent criminal defendant might himself have been released.

From the presented direct democracy Constitution:

Amendment VI – In all criminal suits the accused shall have the right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation upon arrest; to have assigned to the case, upon incarceration, an impartial clerk of the court, at public expense, who shall verify the legitimacy of probable cause by examination of reports and other evidence and a direct, recorded interview of the accused; to attend an information hearing, where said clerk and the accused shall be queried by a judge other than the trial judge, who shall review the evidence and determine which charges, if any, to file; or in the case of an infamous crime, whether to impanel a grand jury and with which indictments pending; to be arraigned before the same court and afforded a plea offer; and, absent a guilty plea, to be informed of the witnesses to and evidence of guilt and afforded a second plea offer; and to be provided sufficient time prior to trial to obtain witnesses and evidence of innocence by compulsory process, with the aid of a publicly funded clerk of the law, while confined or on bail, and at the discretion of the trial judge as to admissibility—to whom any other citizen with probative evidence may submit a request for permission to volunteer the same at trial, after full discovery.

The accused shall enjoy the option of a speedy and public trial, in which the accused alone shall present a defense before an impartial jury of the state and the district wherein the crime shall have been committed; which district shall have been previously ascertained by law.

At any time the accused may waive the right to a trial by jury; or the presiding judge may issue a ruling, upon examination of the accused and with the assent of two mental health physicians, that the accused is incapable of presenting a coherent, effective defense; whereupon the judge may appoint the same clerk of the law to act as a surrogate defendant, enjoying all the rights and privileges of the accused in the presentation of a defense; or may commit the accused to a mental health facility for treatment in preparation for trial.

An examination of prospective jurors and selection of fourteen shall be made by the presiding judge, subject to challenges for cause by the defendant, from among adult citizens whose self-sovereignty never shall have been revoked; and who shall be compensated per hour an amount no less than, but not more than twice, the federal minimum wage, to be determined by the Governors of the states, respectively. The accused shall then dismiss any two of the fourteen jurors by peremptory challenge.

The right to a neutral audience from the jury shall attend the accused; and at the opening of trial the jurors shall be informed of this right and of the nature and cause of the accusation against the defendant; who shall take the witness stand to respond under oath to any germane questions of the presiding judge and the jurors.

The defendant, or the surrogate defendant, shall then call and question witnesses and present evidence, equally subject to the direct examination of the trial judge and the jury, and to the rulings and directives of the former, who shall guide the proceeding in a manner conducive to a full, reasoned and swift finding of fact and law.

Upon the ruling of the court that the defense has exhausted all relevant, material evidence, the judge shall call to the stand for the same full, direct examination any public officer materially engaged in the investigation, arrest or interview of the accused, including the clerk of the court, ending the process similarly with the aforementioned voluntary witnesses and their evidence.

Except in the case of confession the jury shall retire to decide only a general verdict of “not guilty” or “guilty” of the charged, criminal action: All special qualifications and classifications arising from intent or bearing upon sentencing shall be a finding of the presiding judge; who shall follow statutory guidelines in identifying the class and degree of a crime and imposing the designated sentence where applicable; or else exercise the reasonable discretion afforded by law. But no defendant ruled incompetent to present a defense, or having pled insanity as a defense, then found guilty of the criminal action by an impartial jury after a competent defense, shall serve less time in state confinement than could a competent defendant convicted of an equivalent offense.

The inability of more than two jurors among at least nine remaining to assent to the majority verdict after twenty hours of deliberation shall result in a mistrial and a retrial at the earliest, reasonable date. And when, in the judgment of the jury, a material finding of the judge or the sentence imposed is in error or unreasonable, the jury by a unanimous vote may effect the filing of a notice of appeal of the decision, in the name of the defendant.